Towards a clean future for shipping thanks to hydrogen combustion

Shipping accounts for 3.15% of all CO2 emissions. That is not much less than aviation. The good news is that engines that combust hydrogen could be a useful alternative for the shipping industry. In the case of aircraft, that is much less so.

In theory, hydrogen is the ideal fuel. It is relatively easy to make and produces no CO2 when it combusts or is applied in fuel cells. With heavy-machinery engines in particular, such as those used in shipping, hydrogen is a good alternative fuel. That, at least, is the theory. In practice, though, things are more problematic. Using hydrogen safely is complicated. Producing the gas requires a great deal of energy, while the energy density of hydrogen is at least four times less than that of diesel, making it less suitable as a fuel for long intercontinental shipping routes. Together with partners from the private sector, TNO is researching hydrogen combustion in heavy equipment, including ship engines. At more and more locations all over the world, the first experiments involving hydrogen combustion in shipping are now getting underway.

“One of the challenges is that the shipping industry is so diverse. An inland shipping vessel is different to a international freight ship”

A must if we are to achieve our climate targets

Whereas road transport is the greatest polluter as far as CO2 emissions are concerned, transport by water accounts for only a small proportion. Nonetheless, it is important to tackle emissions from ships. That is because it is one of the fastest growing sources of air pollution. During the past two decades, emissions by international shipping have increased by almost 31%, mostly because of the increase in trade. Because of the presence of large ports in the country, the amount of bunkered fuel for ships in the Netherlands is actually slightly greater than for road transport. Making the shipping industry more sustainable is therefore regarded as a must if the Paris climate objectives are to be reached. The International Maritime Organization has established targets for the shipping industry. The aim is to achieve a 40% CO2 reduction for each ship by 2030, and a 50% reduction for all shipping traffic worldwide by 2050. In that context, hydrogen is a major research priority – one that TNO is now actively engaged on.

First step towards sustainability

“We are looking at various options,” explains Jack Bloem, traffic and transport/sustainable vehicles programme manager at TNO. “One first step is to blend 20 to 30% hydrogen with diesel, but to get it up to perhaps 60 or 70%. The advantage of this is that existing diesel engines only have to be modified slightly. This technology could be commercially applied quickly. On the other hand, it also means continuing to emit CO2, and if the shipping sector continues to grow as rapidly as it has been, the benefits for the climate will be less than what you would want. We therefore regard these dual-fuel engines as a first step towards making water-based transport sustainable, for relatively new ship engines for example. This is because they last around thirty years and can be expected to have a long life in shipping.”

“Hydrogen has great potential as a sustainable fuel for the future”

Lack of space for a large tank

The ideal scenario would be a ship’s engine that runs entirely on hydrogen. TNO is also carrying out research into this. “We do not yet know what the best solution is, which is why we are looking at a number of options,” says Bloem. One of the challenges is the highly diverse nature of the shipping industry. Inland and coastal shipping are different forms of transport to international sea shipping and fishing fleets. A drawback to hydrogen is that you need a lot of it (in terms of volume), in comparison to diesel. The tank for a hydrogen engine is seven times larger than its diesel engine counterpart. Today’s ships lack the space for a tank of this size.

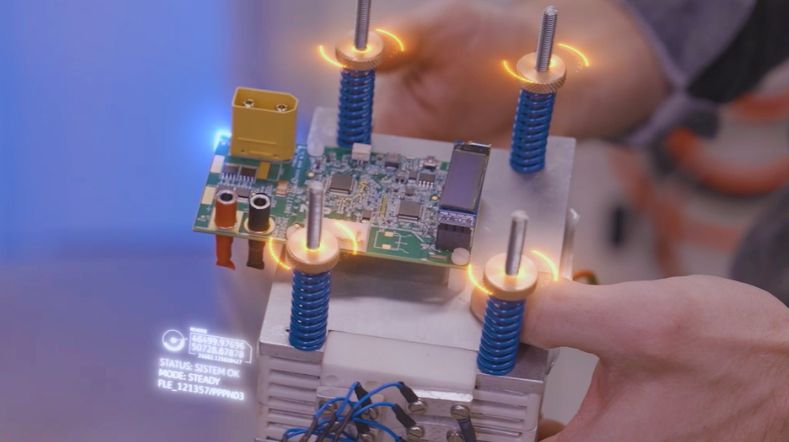

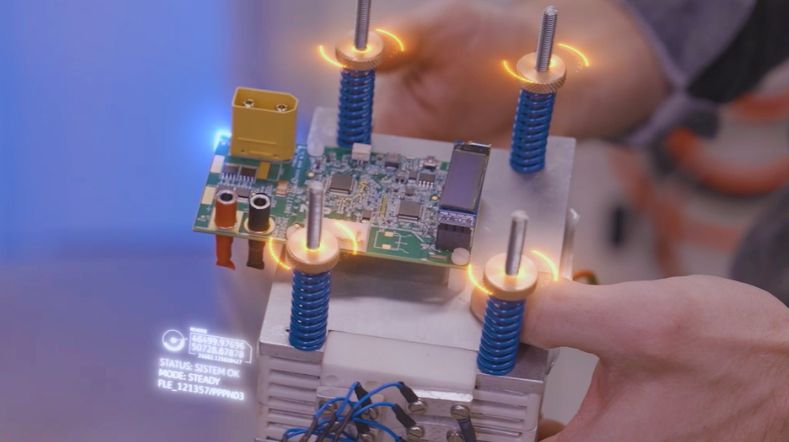

Modifications to engines

An alternative would be to load fuel more often. This makes combusting pure hydrogen more suitable for inland and coastal shipping than for those that operate at sea, which often go weeks without calling in any ports. Bloem: “Engines that combust diesel have been around for more than one hundred years. They have been refined and improved to a high standard since then. Hydrogen is burnt in a combustion engine in a different way to that of diesel. Engines will have to be modified if the process is to run smoothly. The impact on the materials used is also different. Safety on board is of course a serious issue and requires a different set of measures. Various research projects are currently underway at TNO, aimed at the safe on-board storage of hydrogen.”

Packaging hydrogen as methanol

To produce hydrogen, electricity is needed. But as long as it is not generated ‘greenly’, but by means of gas or coal, then hydrogen is not really a sustainable alternative to diesel. Another challenge is the way in which hydrogen is to be used as a fuel. As already mentioned, a disadvantage to hydrogen in its pure form is that its energy yield is low. By ‘packaging’ hydrogen as methanol or ammonia, its energy density increases. TNO is currently researching the application of ammonia in fuel cells. These cells can drive electric engines and have the advantage of causing no harmful emissions.

“We have now reached the stage where the first practical tests using ships powered by hydrogen are taking place”

Sustainable sources

The advantage of using methanol is the size of the tank. Engines that run on methanol require a tank that is twice as large as that for a diesel engine. “CO2 is released when combusting methanol,” explains Jorrit Harmsen, a sustainable shipping consultant at TNO. “But there is a biovariant that is carbon free. You can also make methanol synthetically using sustainable CO2 sources.” TNO was one of the participants on the Green Maritime Methanol Project. It involved a consortium of thirty parties carrying out broad-based research into, among other things, the conversion of engines and storing methanol safely. Various designs were also made of types of ship for which there appears to be great potential for methanol engines. It is now intended that the Green Maritime Methanol Project is followed up in the form of pilot projects.

Pilots with ships that run on hydrogen

Harmsen: “We have now reached the stage where the first practical tests using ships powered by hydrogen are taking place. TNO is involved with two nautical services providers who sail a hydrogen-powered boat on the Amsterdam canals. Elsewhere outside the Netherlands, there is a ferry boat that operates on methanol, too. Several smaller inland vessels are powered by electric motors, the batteries for which are in containers and these are exchanged when the vessels are loaded and unloaded. And there are tests involving the storage and transhipment of hydrogen. But much research still needs to be done. Because the shipping industry is very fragmented, it is unlikely to invest in new sustainable engine technology to the same extent as the car industry has done, for example. This is why it is important that parties like TNO initiate research and work on commercial applications in partnership with businesses in the private sector.”

The Netherlands at the head of the field of hydrogen

Jack Bloem: “Hydrogen has great potential as a sustainable fuel for the future. But it is not just a fuel. You can also use it for creating necessary sustainable energy buffers. This could be in the form of hydrogen (or methanol, DME, or ammonia) in combination with sustainable energy generation. Research into hydrogen is therefore a top priority for TNO. It is important that the Netherlands gets to the head of the field in this technology. We have very many diesel engines so there is a big market. For the Netherlands PLC, it is very useful to have this technology ‘in house’.”

Would you like to know more about hydrogen combustion in the shipping industry? Or would you like to share your ideas in developing it? Then please contact Jack Bloem or Jorrit Harmsen.

Get inspired

How far can you travel in an electric car?

National Growth Fund invests in Dutch battery consortium for heavy duty transport

TNO opens test cell for sustainable marine engines

Battery technology: 4 developments according to the Battery Lab

Fuel cells crucial for decarbonising heavy-duty transport and non-road machinery