Compressed Earth Blocks: an affordable and sustainable alternative to bricks

Compressed Earth Blocks (CEBs) appear on paper to be a promising building material for low and middle-income countries. The pressed blocks are potentially more sustainable and affordable than many comparable building materials. Yet the technology is proving difficult to scale up in practice. Why is that exactly? TNO is investigating this through a demonstration project in Kenya, aiming to identify opportunities for improvement and encourage scale-up. Peter Paul van ‘t Veen explains.

Huge housing challenge

Many low and middle-income countries (LIMCs) are undergoing high population growth, which is increasing demand for housing. On top of that, many existing houses are of poor quality. This means a great deal of new housing will have to be built in the coming period.

Peter Paul van ‘t Veen is the Programme Manager at Innovation for Development (I4D), which aims to improve the lives of people below the poverty line in LIMCs. The programme focuses mainly on Africa. “This housing challenge is an opportunity to ensure good-quality affordable housing and reduce carbon emissions in construction at the same time. If you can replace common building materials with a more sustainable alternative, it can save a lot of emissions.”

Promising new material

One promising building material is Compressed Earth Blocks, made from local soil that is added to cement and subjected to high pressure. TNO has already conducted research into this technique in the past, including in Senegal and Malawi. CEBs could have an array of advantages over bricks and hollow concrete blocks, the most widely used building materials in Africa. While bricks need to be fired at more than 1,000°C, no firing is needed with CEBs.

In addition, CEBs have a higher thermal mass than hollow concrete blocks, allowing them to better regulate the temperature in buildings. They also require less transport, as the blocks are made from local soil. Finally, the technique is quite easy to master, meaning local labour can be used.

Six demo houses under construction

Despite these advantages, the technique is not yet widely used. Peter Paul says, “What we want to know is: what on earth is going on? Why is this technology, which should have such clear benefits, not scaling up?” TNO is exploring this through a project in Kenya, where a number of housing blocks and a school have already been built using CEBs by a Kenyan contractor on behalf of non-profit Habitat for Humanity. Together with Oskam VF, a Dutch manufacturer of loam products and loam stone machinery, and Habitat for Humanity, TNO will be helping to build 6 more demo houses here. The blocks for these houses are produced with a new hand press from Oskam developed specially for handling CEBs for the African market.

Validation of the claims

The most commonly used building material in the region where these houses are being built is natural stone. Part of TNO’s research therefore consists of comparing natural stone with CEBs. Are the claims that CEBs are so sustainable and affordable proving to be true in practice? Peter Paul says, “At TNO, we have a lot of broad expertise on building materials, and specifically on inexpensive and sustainable construction. That allows us to make that comparison. For example, we carried out a Life Cycle Assessment and compared costings.”

“We concluded that natural stone and CEBs are pretty much the same in terms of sustainability and cost. We see that CEBs really prove their worth if we can keep the amount of cement to a minimum. Because it’s mainly the cement that determines the environmental impact and price. The results show us the direction we need to take to make CEBs even more competitive.”

Overhauling the system

In parallel to this research, TNO is surveying the local construction industry, applying the Orchestrated Innovation method to do so. This consists of several steps to identify the different stakeholders, structures, and processes in an ecosystem. “Scaling up CEBs involves more than just producing the best blocks. Also in Kenya the construction world is rather complicated. If you want to scale up a new building material like CEBs, you are really talking about overhauling an entire system.”

“So, we spoke to a lot of contractors, developers, architects, potential financiers, consultants, universities, and of course the people living in existing houses made out of CEBs. We managed to determine what barriers they face when it comes to building with CEBs, but also what opportunities they see.”

“But as I said, it's not just about the technical aspects. We reckon we can gain a lot with knowledge transfer and awareness.”

Removing the barriers

Scaling up CEBs is proving to be complex, as there is no single obstacle. Currently, TNO has defined around 10 potential obstacles. “Going forward, we will be taking a step-by-step approach with the stakeholders to see how we can break these down. One example is by reducing cement use from 10% to 5%, or by using alternative binders. We also expect the new press from Oskam to produce stronger blocks. If we can make gains in these areas, CEBs can truly be a sustainable, competitive product.”

“But as I said, it's not just about the technical aspects. We reckon we can gain a lot with knowledge transfer and awareness. We can also demonstrate that it works ‒ through the demo houses we’ll be building, for example. It’s important for us to demonstrate that we can still ensure quality.”

Scenarios for scaling up

Based on the system analysis, TNO is developing several future scaling-up scenarios ‒ such as partnering with local technical schools, which offer training for masons, finding a local brick or concrete stone factory interested in producing CEBs, or introducing the new construction method to local communities, as in the project with Habitat for Humanity. “If local entrepreneurs learn to produce CEBs independently, it can be a very affordable construction method for them,” says Peter Paul.

On a subsequent visit to Kenya, TNO will flesh out these different scenarios even further with potential partners. Ultimately, TNO wants to create a knowledge hub with these partners to boost scale-up. Moreover, the team wants to explore other areas and countries to put what it has learned into practice there too. “There are several regions in Kenya alone where brick or concrete is the primary construction method. If they switched to CEBs there, it would make a huge difference. I hope we can make strides in the coming year together with local partners.”

Get inspired

Urban mining crucial: more critical and strategic materials from electronics and electrical devices

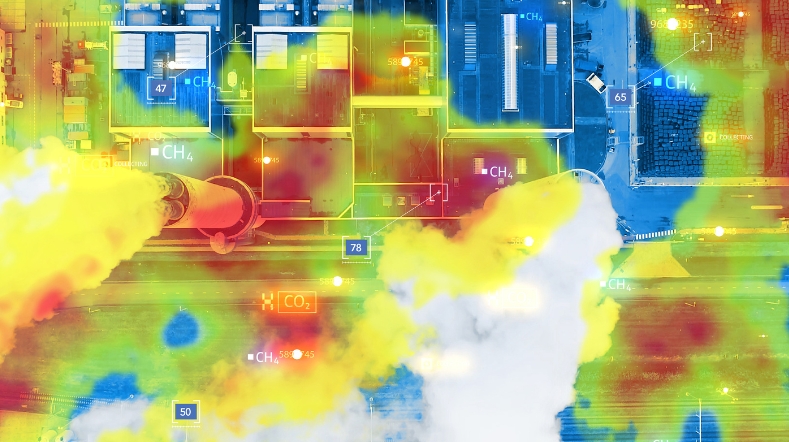

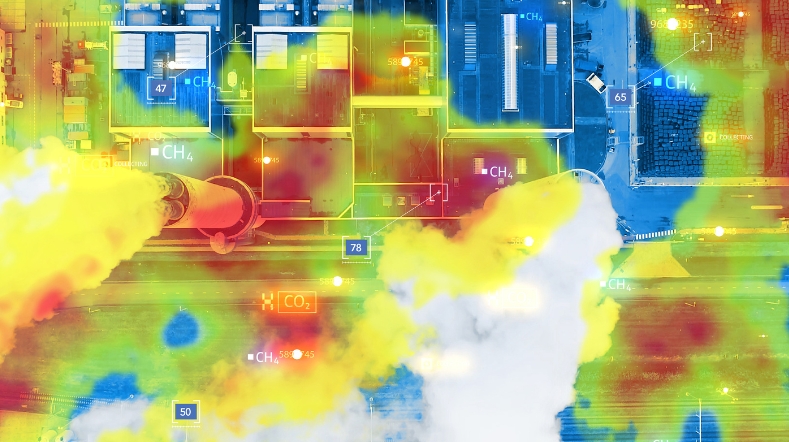

Tracking sources of greenhouse gases with satellites

This is our time: Eleonie van Schreven’s work on small satellites with a big impact

Prospective Life Cycle Assessments for future-proof product design

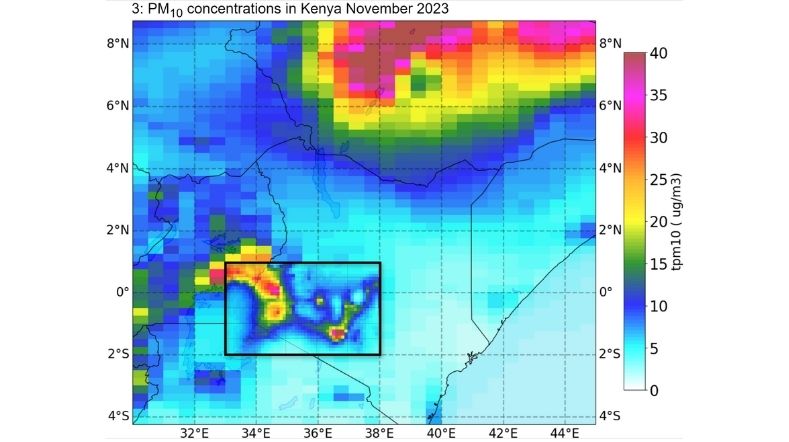

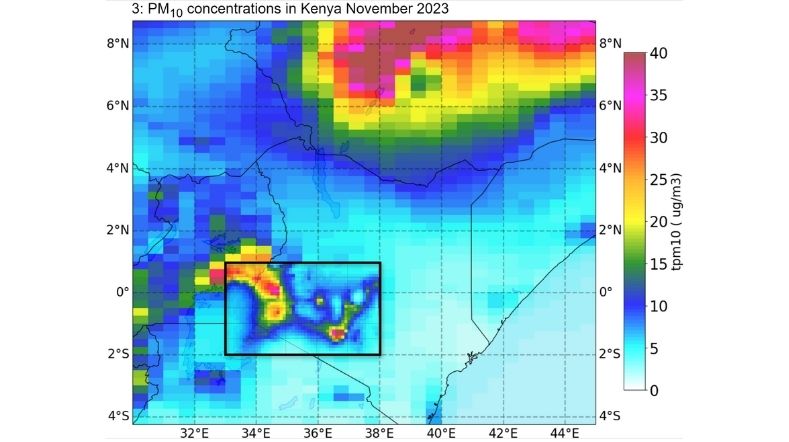

ATACH selects TNO model for climate-related health risks in Kenya